“You have to be a good shapeshifter”

Sometimes the job requires going back into the closet for Bradley Secker, a British photojournalist based in Turkey. In one moment, he feels the need to conceal his sexuality. In another, it’s his ticket to being trusted and telling the story. He reflects on his own challenges of staying safe while also discussing the narrow portrayal of LGBTQ* individuals in the media.

Wissam Farhat, from Damascus, Syria, is gay and waiting for resettlement to a third country, as he no longer feels safe in Istanbul, Turkey. In the past 12 months, there have been several gay men and trans women murdered in the city, both locals and refugees. Photo by Bradley Secker, @bsecker

If you open my wallet, you will find a slightly worn photograph of a woman. When I glance at her image, I smile. This woman isn’t my wife or girlfriend, but a close friend who keeps me somewhat safe from the cloud of homophobia that follows me into the field.

As a photographer based in Istanbul, Turkey, I would have liked to cover the operation in early 2017 to retake Mosul, in neighbouring northern Iraq, but one of the many reasons I didn’t was because I don’t trust the Shia militias that were so prevalent in the battle. Hundreds of men whom they perceived to be gay have been brutally murdered in Iraq since the U.S.-led invasion in 2003.

There are many troubling parallels between the ways we LGBTQ journalists navigate our work and media coverage of LGBTQ individuals and issues. Sexuality and gender identity color too many aspects of these processes, and are often the central factors at work.

“When I’m out in these places, I make sure there’s no discussion about my sexuality,” says a gay colleague who works as a cameraman and photographer for a major television network on front lines around the Middle East. “I used to wear earrings and had piercings, but I took them out,” says M (he asked me not to use his name). “In Iraq soldiers would tease me and say, ‘Are you a woman? You look like a woman.’ I felt uncomfortable and didn’t want that being part of the discourse.”

Self-censorship can be the worst, but if you want to continue covering a volatile region such as the Middle East when you’re an LGBTQ journalist, it’s a survival tactic. I sometimes even worry about having gay and LGBTQ stories on my portfolio website, in case people will suspect me — all this despite being an open, out, and proud gay man since the age of 15.

Even joining Facebook groups and accepting friend requests to avoid awkwardness can be a real matter of security for LGBTQs. Public Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram pages can pose a hefty threat if you’re meeting militia members who want to add you on Facebook or search you on Google upon first meeting.

The positive versus negative balance that my sexuality plays in my work is a tiring but interesting one. It opens endless doors when it comes to covering LGBTQ issues or “softer” stories, but can be a hindrance or downright dangerous when it comes to working on others. Reporters may hope their identity won’t affect the story they’re covering, but it does. It affects how people perceive and interact with you, changing the dynamics of the story.

In the region where I work, the need to keep up the straight façade is always there, hence the photo of my “fiancée” in my wallet. (The woman in the photo carries my photo with her, for those times when being a female journalist garners unwanted proposals and inappropriate invitations.)

In the past eight years, I’ve almost exclusively covered issues affecting the LGBTQ refugee community in my personal work. Meanwhile, it’s easy to become typecast in my assignment work because LGBTQ issues are somehow “my thing,” just because I’m a part of the community. Jake Naughton, a gay American photojournalist who has done work on stories about LGBTQ refugees in East Africa, agrees that this can be a trap.

Cynthia is a lesbian activist and refugee from Burundi. She fled her country after authorities found out she was gay. They beat her and cut her with machetes. Here, she lies in bed with her Kenyan girlfriend in the apartment the two shared in Nairobi, Kenya. She has since been resettled in the United States. Photo by Jake Naughton, @jakenaughton

Soon after arriving in Kenya, S. was attacked by seven men with machetes. Here, he poses for a portrait in the apartment he shared with his boyfriend (though the couple has since been resettled in the United States), with one scar from the attack clearly visible.

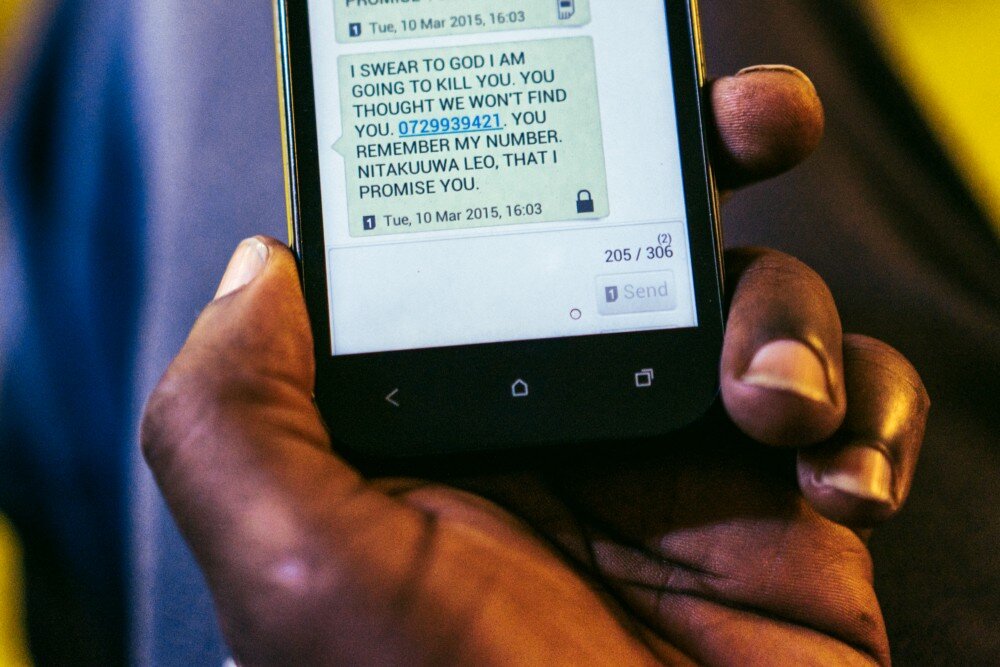

A text message a gay refugee from Uganda received from an unknown number soon after he arrived in Kenya. The sender threatened to kill him that same day, and so he went into hiding. Because he was unsure who sent the message, he lived in constant fear. He has since been resettled in the United States. Photos by Jake Naughton, @jakenaughton

“I don’t want to be pigeonholed into that work, so I am always a bit ambivalent about how much I talk up that work versus my other work,” Naughton says. “But there are so many stories out there about the LGBTQ community that just don’t get told because the world at large paints us with such a broad brush.”

I’ve also noticed a distinct lack of other gay reporters behind the camera. (There are many gay colleagues I know who work in front of the camera, but usually not in the most volatile areas of the world.) I wonder why my gay camera-clad colleagues get drawn into the fashion world, or at least aren’t so prevalent in the world of photojournalism and documentary image making.

An impressive drive for increased inclusiveness has hit the photojournalism industry in the past couple of years. It’s well overdue, and the industry seems mature enough to recognize its own downfalls and see where improvements can be made. At the same time, there have also been a fair number of recent photojournalism scandals regarding image manipulation and misrepresentation, encouraging a particular level of self critique that has helped the industry examine its standards. But it is the debate over and willingness to discuss various perspectives, and grievances, of culturally and linguistically diverse colleagues that is most important, from my perspective. LGBTQ issues have not been prominent in these discussions.

“LGBTQ identity is not one of the checkboxes that the industry is concerned about at the moment in terms of inclusivity of contributors,” says Naughton.

There are grants aimed at stimulating coverage of LGBTQ issues, like those recently offered by the International Reporting Project (which recently announced it was shutting shop), but none aimed specifically at LGBTQ reporters, despite the disparity between the risks we face and those faced by our non-LGBTQ colleagues.

Specific issues affecting LGBTQ reporters, which also affect the LGBTQ population in general, include a much higher threat of mental health issues, violent attacks, and workplace discrimination. These and other subtle uncomfortable feelings can push some to switch to other sides of the photography world, such as fashion, commercial work, or advertising.

“It would be great if there were grants for not just work covering LGBTQ issues, but for LGBTQ photojournalists themselves,” says Matt Lindén, a gay documentary photographer working mostly in East Asia.

Three transgender women take a break to eat ice cream during Teej, the annual festival of celebrating womanhood, in Kathmandu, Nepal. From the series “Tesrolinga.”

A volunteer from the area around Ratsag Monastery, near Lhasa, Tibet, takes care of the butter lamp offering shrine room, located just in front of the main temple. The walls are black due to the soot from the constant burning of butter.

People crowd together at Durbar Square in Kathmandu, Nepal, hoping to catch a glimpse of the “kumari,” the living goddess worshipped in the local Hindu tradition.

Nepal’s first transgender model, Anjali Lama, poses on the roof of the office of the Blue Diamond Society in Kathmandu, Nepal. Anjali works part-time at the Blue Diamond Society, Nepal’s largest and most influential LGBTQ rights organization. From the series “Tesrolinga.” Photos by Matt Lindén, @mattlindenphoto

“The male photographic world can really be quite macho, and I’ve been on jobs with other photographers where I haven’t felt totally comfortable disclosing my sexuality,” Lindén says. “This in turn has made me less likely to go for these kind of jobs and to start doing other photographic work.”

The feeling of exclusion has also been felt by lesbian photojournalist Francesca Volpi, but she says that’s due to her being a woman and not her sexuality. In fact, Volpi doesn’t believe there should be special treatment for LGBTQs.

“I don’t think there should be any less or more chances for homosexuals, or any special grants or prizes reserved for people based on their sexuality,” Volpi says. Instead, she hopes for grants aimed at work covering LGBTQ topics.

A Syrian refugee couple crossing the border between Hungary and Serbia in September 2015.

Young gang members, allegedly belonging to the 18th street gang, or Mara-18, are escorted away during a military police operation in Hato de Enmedio neighbourhoood in Tegucigalpa, Honduras in April 2017.

A family protests against the presence of the Ukranian army near the city of Slaviansk in the rebel held controlled regions in Eastern Ukraine in May 2014. Photos by Francesca Volpi, @francesca_volpi_photo

As journalists we are supposed to remain in the background, and not become part of what we are covering. But as LGBTQ people, I think we have more experience reading people and situations, since we do it all the time for our own safety, which may result in better understanding of a particular event or scenario.

“You have to be a good shapeshifter,” M says. “You can be yourself and openly gay in some places, and not in others. I think we face the same challenges that a lot of colleagues do, but we have a little extra baggage in that we aren’t able to be ourselves publicly. There are worse problems to have.”

M takes this challenge as a motivator.

“This struggle can be the making of us, and it can give us a unique voice and perspective on the world,” M says.

Coverage of LGBTQ issues may be on the rise, but there still isn’t enough deeply reported long-form storytelling. Sure, there’s the annual Pride month news spike, when cliché pieces about Pride marches and joyful partying LGBTQs hit the headlines, but it seems the editorial appetite for in-depth LGBTQ-related stories is minimal.

That lack of appetite can be reflected in poor pay. A major international aid organization once paid me half their usual rate for a series of images of LGBTQ asylum seekers. They said the images were too “niche,” despite then using them widely in their first global report on LGBTQ asylum seekers and refugees, and in subsequent training publications.

Maybe this is just good business on their behalf and not downright discrimination, but slow, in-depth work on LGBTQ lives (like all long-form work) isn’t often given much financial support, despite the subject being in the headlines more than ever before, and despite the aforementioned grants aimed at stimulating coverage of LGBTQ issues.

“Gay coverage in the media is too one dimensional,” M says. “It’s all about gays being persecuted in the Middle East, being thrown off buildings, being put in prison. Look, I think that’s true and happening, but gays are living and having relationships and good lives in these places too. I think there isn’t enough room for those two truths to be told. It’s not one or the other, which takes away from the dignity of gay people everywhere.”

Annie Tritt, a pansexual photographer based in the United States, says there’s a lack of accurate representation of transgender people too.

“I do think there is a lot about gay people, but much of the work about trans and nonbinary folks is stereotypical and uninformed and that needs to change,” Tritt says.

One of Tritt’s series, called Transcending Self, focuses on young transgender people. The portraits depict transgender life between the ages of 2 and 20 years old, giving a wide range of opinions and personal experiences from those photographed, as well as their parents.

Tritt tells me, “I put so much time into this project because it matters. Trans youth have a suicide attempt rate of almost 50 percent, yet when they are supported, it drops to close to that of their peers. The murder rate of trans people is close to one every two or three days worldwide. This is based in fear.”

Justin, 8, a transgender boy and his brother in northern California. “He was sure (about being a boy) and in my heart, I was sure too,” says Justin’s mom. “When your child tells you something like that, you know it’s real. You know in your heart they can’t live any other way, or they would not be able to be true to themselves. I told Justin I will always love you no matter what. Whether you are a boy or girl I will always love you! Since Justin has become Justin he lets me hold him and cuddle with him. Before the transition, Justin would barely let me touch him. I think that he is happier as a boy.” Justin’s dad says, “I didn’t sign up for this. But I’m in it for the long haul. I’m scared at times. I fear for his future. I want him to be happy. I want him to be accepted. I want him to have friends. I want him to believe that anything is possible. I want him to know that he is loved.” From the series “Transcending Self.” Photo by Annie Tritt, @trittscamera, @transcendingself

These are jolting figures, which is why Tritt says she’s so determined to focus on telling these stories.

“I hope that it helps young trans kids feel good about themselves, that parents embrace their kids, and teachers, doctors, and strangers have more understanding,” Tritt says.

Changing how LGBTQs are represented in media coverage is one challenge, another is to address attitudes towards LGBTQ colleagues in the newsrooms and in the field. I don’t believe the industry is actively discouraging LGBTQ people from being part of its ranks, but is it really doing enough to push for more inclusiveness?

“I think people are very careful nowadays in saying or doing things that can come across as homophobic,” Lindén says. “However, that doesn’t mean that behind the scenes, one’s sexuality isn’t changing their perception of what we’re able to do.”

Most of us would be challenged to name more than a few lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender photojournalists, and maybe there is a reason for that. If you don’t want to continuously hide elements of yourself, getting temporarily dragged back into the closet, then I can understand why you wouldn’t choose photojournalism as a career path.

LGBTQs may be a minority of the population, but we cross all socio-economic, class, ethnic, and geographic lines, meaning we are present in all areas of society, and have an equally wide array of stories to tell from within it.

Though I’m writing about the experience of being an LGBTQ photojournalist, I imagine that in most other highly competitive fields, you would find similar challenges for LGBTQs. It’s not that photojournalism is downright unwelcoming or inherently straight, it’s just an industry that needs to open its eyes to the diversity in its ranks in order to attract more.

A former Syrian police officer who defected lies injured in an area under opposition control as he waits to be taken to a makeshift field hospital to treat his broken arm and leg. 2

Şükriye İletmış, 70, in her garden in the village of Hasköy, near Izmir, Turkey. Şükriye identifies as an AfroTürk, and her story is featured as part of my ongoing work on the little-known community in western Turkey.

Egyptians gather in Tahrir Square in central Cairo to celebrate the overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood government by the military in 2013.

A couple sit at home with a friend in their village in the southeast of Turkey. The village is almost deserted as the majority of the population has moved to bigger towns and cities for work. Photos by Bradley Secker, @bsecker

“There must be a ton of photographers that are gay, but they’re not ‘gay photographers,’” says M.

And that’s how it should be — sexuality should be irrelevant when describing someone professionally. I hope more LGBTQ people decide to become photojournalists — not to tell more LGBTQ stories, necessarily, but to add their way of seeing the world to the mix, to break down a few more barriers in the industry, and to help add nuance to how LGBTQ individuals and stories are covered, if they do cover them.

*I’ve used the acronym LGBTQ in this article, but this isn’t supposed to exclude. It’s a shortened version of the often-longer acronym that can be LGBTTQQIP+.

Hussein Sabat, winner and title holder of Mr. Gay Syria 2016, stands in the doorway of a gay-friendly cafe near Taksim Square, as Turkish riot police pass by to prevent the LGBTQ Pride March from taking place. The 2016 march was banned, citing security concerns. Photo by Bradley Secker, @bsecker

Bradley Secker is a British freelance photographer based in Istanbul, Turkey, since late 2011. Covering news and features, as well as personal projects, Secker’s work often focuses on the consequences of social, political, and military actions. He also looks at how identity shapes lives in challenging and unexpected ways. Follow him on Instagram.