In Conversation with Janet Jarman

Mexico-City based photojournalist and filmmaker Janet Jarman has been taking pictures since high school. Re-Picture editor Elie Gardner interviews Jarman about her initial hesitancy to embrace audio and video — and how it eventually led to her current project, a documentary film funded by the MacArthur Foundation.

Members of a private Mexican family’s professional security team travel behind their boss’s car, poised for potential action. As a result of Mexico’s persistent violence, many of the country’s elites choose to take protection into their own hands, by hiring private security teams and bodyguards. Photo by Janet Jarman, @janetjarman

Elie Gardner: How would you describe your leap from being a photojournalist to being both a photojournalist and filmmaker?

Janet Jarman: A recent statement by a close friend sums up how and why I started my journey from shooting exclusively photographs, to employing a combination of still photography, audio, and video on many of the projects I produce today. She said:

“I do what scares me. It’s the only way I can grow.”

I have always believed that visual journalists who could employ a variety of skills would have more opportunities in an increasingly competitive editorial journalism market.

In what would turn out to be a pivotal decision in my career, I embraced the potential of the multimedia approach to storytelling. I wanted to be at the cutting edge of my profession, and I didn’t see a contradiction in simultaneously using two related, but very different skills to tell a story. Since childhood, I had resisted being put in a neatly labeled box. So why start now?

EG: As a photographer, were you hesitant to pick up a video camera? Why or why not?

JJ: I vividly remember my skepticism years ago, when news organizations, mentors of mine, and eventually clients began to encourage video storytelling. I made it clear to everyone close to me that I would never use a video camera. I didn’t like the picture quality that they generated, and I couldn’t imagine abandoning my still cameras. They had been like trusted friends for many years. Why was it necessary to switch to video, I thought? Why did images need to move?

Antonia Rojas, 13, quietly watches Day of the Dead celebrations in the village cemetery in San Pedro de la Laguna, near Patzcuaro, Michoacan. She clutches traditional flowers, including marigolds, which are perhaps the most ubiquitous symbol of Mexico’s widely celebrated Day of the Dead tradition.

A boy stands in the courtyard of his home in the small Maya community of Santa Cruz Obispo, in Mexico’s Chiapas state. Sergio Castro, known by most as “Don Sergio” built a water system in this community with help from a U.S. foundation. In 1966, Castro began working in Chiapas as an agronomist and veterinarian. After witnessing alarming conditions in many isolated villages, he tried to help by building schools and potable water systems. He also taught himself to treat complicated wounds, and filled a void in the public healthcare system.

Guests dance with the bride and groom at the beginning of a wedding reception that lasted into the early morning in San Antonio de Lourdes. The remote village in the north of Mexico’s Guanajuato state is among many with grave water problems, including lack of water and extreme levels of contamination of groundwater, often making parties and festivals unaffordable for residents who take pride in maintaining their strong Catholic traditions. Photos by Janet Jarman, @janetjarman

I was convinced that only the still photograph had the power to make people stop, feel, and reflect. Motion seemed like a bombardment of information that could result in passivity. If I decided to pursue motion, would I be contradicting myself and betraying my craft? Could I still be true to my way of storytelling? The answers would reveal themselves, years later.

As a still photographer, I used to observe television and cinema crews when we coincided on assignments. Their equipment seemed complicated and heavy, and they could hardly be as discreet as I liked to be. I thought I could never understand life on their planet. But in retrospect, I must admit that I was daunted by video technology and editing.

Sound, however, did fascinate me. While driving all over south Florida during my first newspaper job, I frequently listened to public radio. I loved how radio journalists made stories come alive using ambient sounds and poignant interviews. It was as if a person’s voice and form of expression seemed equal to the power of light or gesture in a photograph, and a unique natural sound could take me closer to the essence of a situation.

EG: In 2006 I was working at a newspaper where it was decided that the entire photo staff would be trained to record audio and, eventually, shoot video too. What do you think lead to decisions like this and so many photographers picking up audio and video recording skills in the past decade?

JJ: Lightweight digital audio equipment had become financially accessible and learning these tools was intriguing. I, for example, purchased a small DAT recorder and started to experiment with personal projects. The combination of audio and still photographs felt like a great match.

Mihaly Basci, 84, visits his son’s home in Nyritelek, Hungary. Basci is a Roma Gypsy. Historical patterns of prejudice and discrimination have long isolated Roma communities. The socio-economic conditions of the Roma in Hungary are among the worst conditions facing any ethnic group in Europe. Photo for Ashoka by Janet Jarman, @janetjarman

The idea that multimedia would conquer all in its path didn’t catch on immediately, for many reasons. However, I must confess that I felt a new surge of excitement the first time I did a project for which I shot stills and recorded audio interviews, and I felt strongly about pursuing this approach in more depth. Multimedia visionaries Rich Beckman and Brian Storm actively encouraged me in this direction.

I had the chance to speak with Storm and Ed Kashi on a panel at Visa Pour l’Image/Perpignan in 2004, about the future of multimedia. Would this new form of storytelling become a threat to our cherished still photography? No, we said, because photographers and journalists would still have to deliver compelling stories. Only the tools were changing, and we believed these new tools could actually make us better photographers and better journalists.

EG: Tell me about your first professional experience with multimedia.

JJ: Surprisingly, my first multimedia project did not come from an editorial client, but from nonprofit Ashoka. In 1998, I cold-called their marketing people after reading about their social entrepreneur fellows programs around the world. They agreed to see me, and during a brainstorming meeting in Washington, D.C., they proved receptive to my suggestion that they could invigorate their online presence by creating slideshows underpinned by interviews with their fellows, who they called “Changemakers.” They loved the results and sent me to profile their fellows all over Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Americas.

EG: Tell me about your multimedia trajectory in the months and years after that first project.

JJ: In Guerrero, Mexico, I spent a week documenting the work of a social entrepreneur in a coffee growing village, and I felt the potential for an editorial, long-form story about the challenges facing the small-scale coffee farmers in Mexico. I took material to Storm at msnbc.com. He liked the idea and assigned Meredith Birkett-Hogan to work with me on a story called “Coffee Crisis.” I was convinced after this project to continue working this way, since it allowed me to use more journalism skills in a multi-layered, nuanced approach.

Reina Isabel Guido leads her group to one of the highest points of Finca La Revancha in the early morning. La Revancha became the first Fair Trade certified coffee estate in Central America in November 2013.

After a long day of picking coffee, Juan Torres, 60, rests on the wooden planks where he sleeps, inside a room he shares with other workers on a coffee estate near Matagalpa, Nicaragua.

In Chiapas, Mexico, a group of Guatemalan coffee pickers gather around their daily coffee harvest to sort through thousands of cherries, separating the unripe green cherries which will undergo different processing into lower quality coffee. The once-processed beans from the green cherries are sold for less than a third of the red cherry price. They are usually processed into instant coffee for national consumption, not for export.

Guatemalan coffee pickers convene around a morning fire to warm the breakfast that will sustain them during a long day of harvesting coffee cherries in Chiapas, Mexico. They come yearly to this farm from northern Guatemala. Photos by Janet Jarman, @janetjarman from the story “Coffee Crisis”

Over the next 13 years, I progressed from creating photo slideshows with audio, to transitioning into producing short video stories for editorial clients and nonprofit organizations. I still had mixed emotions about shooting video, but once the motion quality of DSLR cameras was satisfactory and editing software became affordable, there was just no longer any rationale for not shooting video for my web-based stories. I had run out of excuses.

EG: What was your first professional video assignment?

JJ: In 2010, The Knight International Media Center at the University of Miami gave me my first opportunity to put video in the mix when they commissioned me for “Aguas Negras”, a project on Mexico City’s water problems, and I experimented with editing together video and stills. It was an elegant way of easing my way into motion.

Alperio Jaramilla Gonzalez transports water to his animals several kilometers from his home, in the village of El Vergel, in the arid hilly lands of northern Guanajuato, Mexico. The daily trips are especially important during the area’s driest months of March, April and May, when nearly all water sources in the area have dried up before the rainy season starts, typically in late May or June.

Built up detergents in wastewater form immense mounds of foam as Mexico City’s black water (sewage) flows through a small irrigation canal in Mezquital Valley, where farmers use the untreated wastewater to irrigate crops.

Workers excavate inside one of 24 shafts that form part of the Tunél Emisor Oriente, one of Mexico’s most dramatic water infrastructure projects in 30 years. The shafts are designed to provide ventilation and to allow the introduction of machinery during and after the project’s completion. The seven-meter wide, 62-kilometer deep tunnel was constructed to duplicate drainage capacity in the Valley of Mexico and prevent serious floods that occur throughout the Mexico City metropolitan area.

Rosario Martinez attempts to remove water from her apartment, flooded after torrential rains caused an open drainage canal to break and propel raw sewage into streets and homes in Colonia Ampliación Emiliano Zapata. The low-lying area is one of the most flood-prone areas in Mexico City.

Various potable water vendors and suppliers circulate in front of a micro-purification plant in Iztapalapa, where some of the most damaging effects from Mexico City’s water crisis are felt. Photos by Janet Jarman, @janetjarman from the story “Aguas Negras”

EG: Since then, how have you balanced still photography and multimedia assignments? And what have you gained from taking on more than still photography?

JJ: Most of my editorial assignment work, at that time, remained still photography only. However, emboldened by the Knight water project, I started to generate newsworthy story ideas for which I could produce both a photo slideshow and a video.

I pitched these ideas mostly to the Mexico bureau chiefs, world desk picture editors, and video editors at The New York Times. Getting everyone on the same page for an ambitious story that was not initiated ‘in-house’ was often difficult, but eventually, with helpful nudging by the writer, the newspaper took on some really adventurous projects, such as Police Reform, A Passion for Healing, and Calling the Midwife. On every one of these projects, I felt like I was constantly re-inventing myself, opening new ways of thinking and seeing.

I started the police reform story as a still project, but as soon as I saw the exciting action in front of me, I quickly flipped the switch on my Canon 5D Mark II, and I started shooting video instead. I will never forget that moment when I became unafraid to choose still or motion, depending on the situation. I would keep experimenting with that approach for a number of years.

I was pleased that these stories were published in The New York Times, and I enjoyed working closely with both their photo and video editors. But the vision that multimedia was the ‘wave of the future’ and that people who had both photo and video skills would have a leg up faced a rude reality check.

Instead of receiving kudos for bringing the client a “turbo-charged” visual journalism project, where I had generated the idea, secured the access, and offered both a comprehensive slideshow and a compelling video, I sometimes felt that editors considered my approach overly ambitious. The stories I brought them worked out well for the New York Times and won some industry awards, and I had hoped that more such projects could emerge. However, cross-over assignments for which the same person would provide both photos and video were rare, at least for freelancers like me.

EG: How did these experiences affect how you approach storytelling today?

JJ: After the only lukewarm editorial buy-in to my hybrid style, I started to wonder if I should even continue to propose ideas to this type of client. On the one hand, I saw tremendous value in using this approach to tell the stories I cared about, such as women’s rights and the environment. But on the other hand, working on projects using motion and stills was very time-consuming and equipment-intensive compared to photography alone.

I sometimes still felt overwhelmed by the rapidly changing technology, and I was frustrated that editorial budgets barely covered the production costs of multimedia projects.

I also worried that I could not be as networked and prolific as many of my peers who could take on assignment after assignment while I was sometimes spending many lonely months on long-form multimedia projects. Did spending all this time and energy to create photo-video projects for editorial clients really make sense?

I decided then that for my editorial clients, I would focus strictly on still photo assignments. If these clients asked for video, I would be more than happy to do so, but for the most part, I would focus on video storytelling for my nonprofit clients. This may all sound logical in hindsight, but for a few years there, I really thought that I had a chance to contribute to a new way of editorial storytelling. Too bad that it turned out to be a bit of a chimera.

Wearing his signature black sombrero, Dr. José Manuel Mireles gives a motivational speech to residents in Tancitaro, days after the town, located in the mountains of Mexico’s Michoacan state, liberated itself from the oppressive drug cartel that called itself the Knights Templars. Mireles led a movement to unify and assist self defense vigilantes to protect themselves against the cartel and drive all criminals out of their communities.

In the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico, traditional midwife María López Gonzalez checks the abdomen of her patient Rosita Gonzalez López to see if her baby is in the right position. For generations, the indigenous women of Chiapas have had their babies delivered at home by midwives. If Doña Mari feels that something is seriously wrong during a woman’s pregnancy, she takes her to a nearby government health clinic.

Sergio Castro makes a house call to a terminally ill resident in San Cristobal de Las Casas in Mexico’s Chiapas state. The patient and his family are among many who trust Castro more than they do public hospitals. Castro previously treated predominantly burn victims from rural Mayan communities, but his reputation followed him to the city where families seek him out to treat any type of wound, including bedsores and diabetes ulcers. Photos by Janet Jarman, @janetjarman

EG: Do you think it is practical to be both a photojournalist and filmmaker?

JJ: It may not be practical to try to be a hybrid photojournalist/filmmaker simultaneously. It is very difficult to be both at the same time, due to the demands of each process. I have come to realize that I have a different mindset when shooting stills and video. For stills, I am seeking to capture the essence of an entire scene, conveyed in a single moment. For motion, I am thinking of how to paint a scene through a succession of wide, medium, and close-up images. The equipment is also different. I now use a dedicated Canon C300 cinema camera for motion most of the time, and my 5D Mark IV for still shooting.

I do love shooting motion now, but my photojournalistic eye still directs the core of my style. I am not a distant observer. I want to be inside a scene, where emotion is being experienced. I want to be present, spontaneous, and in the moment. I want to capture the essence or truth in the situation and portray it in a balanced way. That is what I have always tried to accomplish with my work; to achieve access in delicate situations, and to make viewers feel like they are there with me. That is my visual storytelling style, and I am translating that to my motion work.

EG: Has your journey borne fruit?

JJ: I hope the answer is affirmative, although I will never know what my career might have looked like had I doggedly remained a “pure” still photographer.

The past few years have revealed how some of the pieces of the puzzle are coming together. I continue to be commissioned for interesting still assignments, and gradually, my short films are being noticed. The videos I did for the New York Times serve as a springboard to being offered more ambitious and longer projects, such as the film “Con Madre” with Christy Turlington’s nonprofit Every Mother Counts. This film was recently published on National Geographic’s Short Film Showcase.

EG: What are you working on now?

JJ: I was thrilled when the MacArthur Foundation awarded me a substantial grant to make a feature-length documentary and photo exhibit about maternal health challenges in Mexico. I have been producing this film for over a year now. The project is a culmination of every journalism skill I have learned and everything I have been striving towards for the last 15 years. Working with my small team on this vast topic can be scary and exhausting, but exhilarating at the same time. I can’t wait to share the film and exhibit in 2018 with a wider public.

These photos are from a two decade-long story about Marisol, who migrated to the U.S. with her parents and nine siblings in 1996. 1) Marisol and her son Carlos interact inside their living room, days before she gave birth to her second child, a daughter named Anahi, in 2007 in Texas.

Marisol daydreams at dusk while anticipating the arrival of more garbage trucks at the municipal garbage site where she and siblings search for recyclable items to support their family’s income in 1996 in Tamaulipas, Mexico.

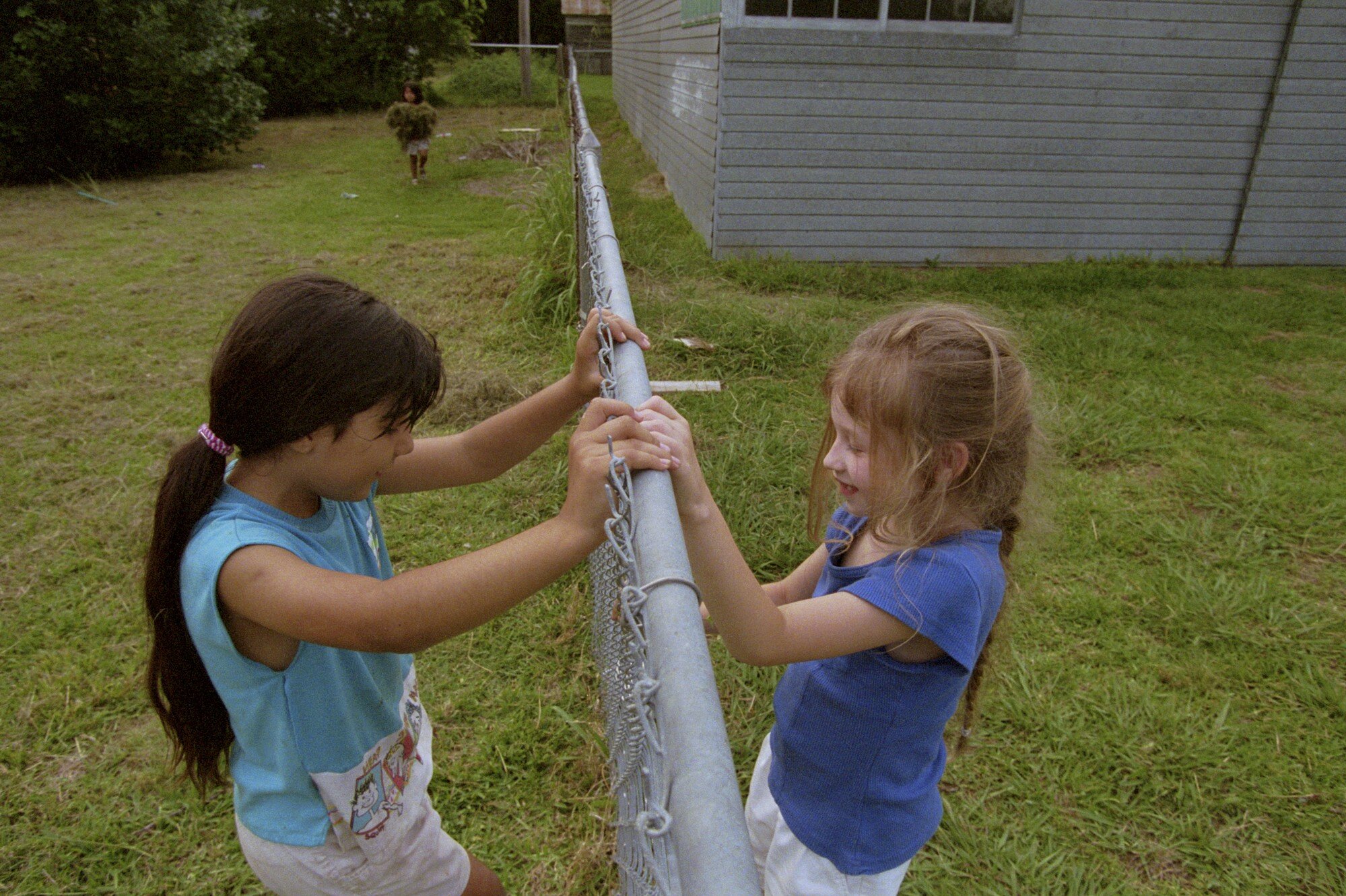

Through the fence that divides their families in Texas in 2000, Cristina (Marisol’s sister) and Mary become friends even though Mary’s parents prohibited her from entering the yard of her Mexican neighbors. Immigrants must first cross a geographical border. Afterwards, they often confront many other challenging social barriers. Photos by Janet Jarman, @janetjarman

EG: What advice would you give to photojournalists considering learning additional skills, such as audio and video, today?

JJ: Success depends first on being a strong storyteller. No matter how much equipment you add to your creative tool set, being an experienced journalist and storyteller will set you apart. Master that first. Knowing how to conduct revealing interviews, how to find interesting situations and how to create stories that have a compelling narrative arc is paramount. It is sometimes easy to get lost in the technical challenges of filmmaking, but once you pull your focus back to the story, magic can happen.

This article is published by Re-Picture, an online publication of The Everyday Projects. The Everyday Projects is a network of journalists, photographers, and artists who have built everyday social media narratives that delight, surprise, and inform as they confront stubborn misperceptions. We believe in developing visual literacy skills that can change the way we see the world by challenging stereotypes. Find out more about The Everyday Projects here or feel free to get in touch: contact@everydayprojects.org.