“When living is a protest:” Ruddy Roye on overcoming pain through pictures

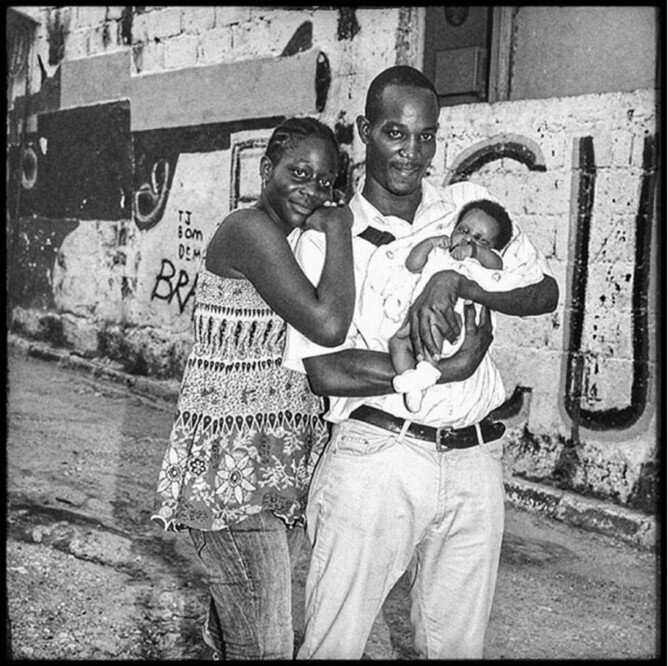

Photos by Ruddy Roye from his Instagram account, @ruddyroye.

Photographer Ruddy Roye says he’s always been tied to people and their relationship to their environment. His first photography project took him 121 miles on foot along a defunct railroad line in his home country of Jamaica, documenting the lives of those who lived along it. “Wherever I’ve lived, I’ve photographed the way people interact and engage with their community,” he said.

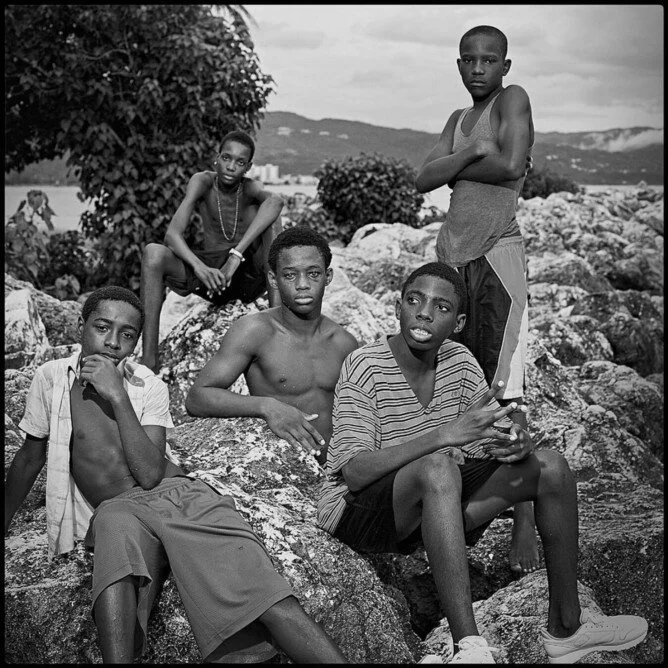

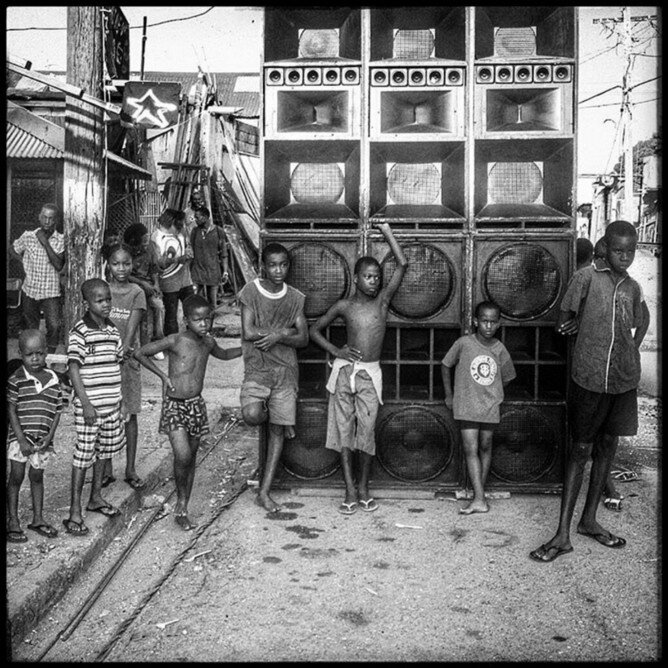

Photos taken by Ruddy Roye in Jamaica.

In 2000, Ruddy moved to the United States as a stringer for the Associated Press. In his free time he photographed the streets of Bed–Stuy, a neighborhood in Brooklyn that has historically been a cultural center for New York City’s black community. Ruddy was compelled to pick up his camera because he would see images that hadn’t changed in 17 years. “I just couldn’t pass [them by],” he said.

It was the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2012 that finally pushed Ruddy to take his message — both in photos and words — to Instagram. On social media, a space free from editorial constraints, he could openly express his thoughts about the racial injustices that continue to plague and traumatize black communities.

“The work is about conversation. I want people to talk about it — both black and white people. I don’t want white people to be silent. We’re too silent.”

With some images garnering anywhere from 20 to more than 100 comments, his images certainly achieve that. But perhaps the response from followers is a reflection of what Ruddy himself puts out: his photos are paired with long, eloquently written pieces of text — something nearly unique among photographers.

Photographs by Ruddy Roye from his Instagram account.

“I’ve always known what the historical context or the iconography of the black image has always been — the thug, the over-sexualized female. I didn’t want anybody to wrestle with what I was photographing…I want them to know that this person is also a human being, this person is also your cousin, your aunt, your uncle, your brother, your mother, your dad. This person’s only difference is their color.”

Comments range from short exclamations of love or inspiration to others that reflect deeply on Ruddy’s message. In one recent post, Ruddy rhetorically asked, “Why are you so silent?” One viewer responded: “Thank you for your question. It’s one I don’t know the answer to but it’s making me look at myself and really ask…why am I so silent…with all that is going on. Why am I not speaking up and I don’t live in your country but I am a citizen of the world. So I suppose my answer is not so much w/ my words but my actions henceforth…thank you for not being silent. I love your voice @ruddyroye.”

Other times, the comments get personal. Ruddy said one follower poignantly described how his work affects him on an intimate level. “It’s painful and there are times when I’m hurting,” he said.

Ruddy believes the ability of people to push past this pain on a daily basis is their form of protest. “The fact that [people] refuse to go under, refuse to give up, that is a protest to me.” Many of his images include the hashtag “When Living is a Protest,” which is also the name of his first solo exhibit on view at the Steven Kasher Gallery in New York City until Oct. 29.

Two of the images on display in Ruddy’s first solo exhibit at the Steven Kasher Gallery in New York City.

“We’re in a crisis, we’re in an emergency. It’s going to take something very surgical, very intentional, very precise. It’s going to take cooler heads, it’s going to take forgiveness, it’s going to take want and kindness to push past all this ugly and this racism and this strife,” Ruddy said in response to how the situation for black Americans will improve in the US.

Photograph by Ruddy Roye from the Inauguration of the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington D.C.

According to the Washington Post, “black men account for about 40 percent of the unarmed people fatally shot by police and, when adjusted by population, were seven times as likely as unarmed white men to die from police gunfire.” African Americans are imprisoned five times more than white people, and author Monique W. Morris has written of the many ways black Americans are affected by institutionalized racism.

“Imagine what it does to the psyche, imagine what it does to a kid who is teetering on giving up or looking for a way out and what he sees every day reminds him that there’s no escaping [it]. Like this is it, this is his lot in life. His lot in life is one corner [and on] one corner are the guys on the street selling drugs and on the other corner is the alcoholic and the difference between those two corners is just a couple of years,” Ruddy said.

Through the power of photography, Ruddy hopes to stimulate people and to change the way they see, react and think about black lives. “They’re not an entity outside of themselves, they’re not something otherworldly…it’s not that you’re just helping black people, you’re helping humanity. We are part of humanity.”

“When Living is a Protest” will be on exhibit until Sat. Oct. 29 at the Steven Kasher Gallery in New York City where Ruddy’s images are on sale. A percentage of proceeds will be donated to Black Lives Matter.

Ruddy Roye is a photographer and founder of Everyday Black America and Everyday Jamaica.